The unimaginable that becomes your reality

The morning after I found my dad’s body, and the notes he had left us, I got my children up and ready for school as usual.

I hadn’t been able to bring myself to tell them that their beloved grandad had died, much less that he had taken his own life. I think I was completely on auto pilot, and partly it was that I just could not face that obvious question from young children: ‘why?’.

I simply had no answer for them - and I’m not sure that I have any answers still, 25 years on.

My dad was 67 at the time he made his choice to die by suicide.

At that time, I was a married mum of two - the children were 9 and 5 - and I was working part-time. In fact, the day I found Dad I had just left my job and was due to start a new one on the Monday.

He and my mum had divorced and he was living alone, and some friends had been in touch to say he hadn’t shown up for a lunch, as well as an AGM meeting he had been due to attend. I'd assumed it was because he’d had a bit of a cold, but thought I’d pop in and check on him.

I remember walking through the door and I saw him. I think I screamed. I remember shutting the door and going to a neighbour’s and saying, I need to call 999 because my dad’s died.

I also remember what felt like an immense responsibility of having to break the news to my brother and mum, knowing the phone calls I was going to make were going to cause such pain - how on earth could I spare them from the pain I was in at that point? But of course, I couldn’t.

It was just the biggest shock: the unimaginable that becomes your reality.

"It became clear he'd been planning it"

The timing of it seemed really strange. The last time I had seen him, a few days previously, he’d been absolutely full of the joys of spring. He’d come to watch my son take part in a scout gang show, bounced my daughter on his knee - he was the life and soul. He had been a little bit low before, some issues with some neighbours that had been getting him down, but I actually remember thinking that night, I’ve got Dad back.

The timing of it seemed really strange. The last time I had seen him, a few days previously, he’d been absolutely full of the joys of spring. He’d come to watch my son take part in a scout gang show, bounced my daughter on his knee - he was the life and soul. He had been a little bit low before, some issues with some neighbours that had been getting him down, but I actually remember thinking that night, I’ve got Dad back.

Much later on, I would learn that this can be a classic sign that someone has made their decision to end their life. It also became clear he had been planning this for some time; he had been to the bank to sort some things out, he’d left some letters for me and my brother and some friends.

From the letters, it was like he blamed us for taking sides in the divorce (we hadn’t). They were really hard to read, and it really hurt. I’m not sure that my brother ever got over that. And my mum, his ex-wife, also really struggled, almost felt responsible, like he had taken his life because of her.

There is something about the nature of suicide that makes it such a shocking reality to come to terms with. I really struggled to sleep; I just couldn’t get that image of my lovely dad out of my head.

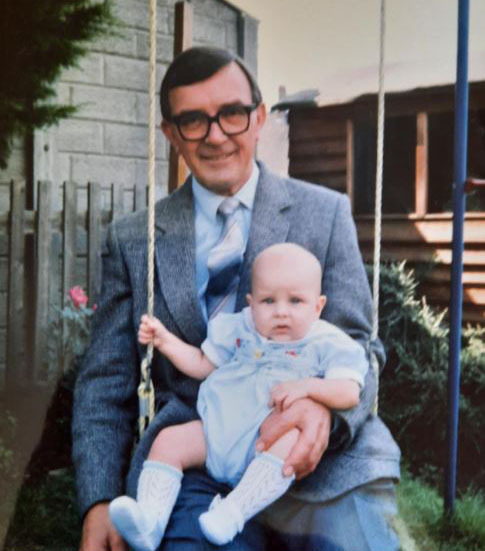

I went to my doctor and I said, I just need to be able to sleep - I have this picture in my head and I need to be able to not see it. He was probably quite ahead of his time. He said no medication would ever take that away; what I needed to be able to do was replace it with a better image. He suggested I have a nice picture of my dad, the way I remembered him, next to my bed, and every time I thought of the bad image, I should look at that - eventually one would replace the other.

In a way the fact that I had two such young children and my mum to worry about meant that my coping mechanism was to just keep going; I didn’t get to grieve. I didn’t start that new job on the Monday, of course, but I did start a couple of weeks later and I really needed the normality of that and the routine of sorting out the kids to muddle my way through the next few months.

When I did take my foot off the gas, that summer, I did let go. I had a breakdown and was diagnosed with clinical depression, which was medicated. I was offered some bereavement counselling. This included some group therapy with others who had lost people to suicide and some of those stories have stayed with me - the people who were still thinking about an argument they’d had a few days before, the woman who had lost her son 20 years ago and said she still asked herself ‘why?’ every day.

"The ripple effects of suicide are so far-reaching"

At that point, I thought, I need to make my peace with that aspect. That’s not how I am going to deal with this. All of the professional advice had been that I should tell my children how their grandad had died, but I chose not to - life returned to a different type of normal, the kids would ask to go and see ‘grandad’s rose bush’ at the cemetery, we’d talk and laugh about him often.

I didn’t want their memories of him to be sullied and, most of all, I wanted them to have a childhood that was not defined by this.

I don’t understand Dad’s choice, and I probably never will, but I had to make my peace with that. I stand by my decision to handle it that way with my children; I was prepared for them to hate me when they eventually learnt the truth, as adults, but I would make the same choice again.

The loss of my dad pushed me to do more to understand mental health, perhaps in a way I would not have otherwise. He was a very old-school man, used to say ‘boys or men don’t cry’. More recently, having done mental health first aid training, it was like light bulbs going off. I started to understand how it had affected me, my ex-husband, my mum and brother. I began to understand I am only responsible for myself.

The ripple effects of suicide are so far-reaching. With any bereavement you will have people who don’t know what to say, but it’s like the subject of suicide takes it up another notch. I had friends who didn’t know for years because it just doesn’t make for easy conversation.

The thing I wish more people knew about suicide is that it is such a permanent end to a situation that may be temporary, even if that pain feels unbearable at the time. I don’t think I ever felt angry, I just felt bewildered and sad. He had children and grandchildren that loved him and has missed out on so much.

My message to anyone who has experienced a similar loss is that there are other people who have experienced this and it helps to reach out. There are also charities like Samaritans, Cruse, and SOBS (and LionHeart, of course, if you’re from the surveying community). You will learn to live a different kind of life: there will always be something missing, but life will go on.

I’m happy to share my story if it helps one person, somewhere, to deal with the unimaginable pain that is suicide.

Christine Pennington is LionHeart's executive assistant. She is also a qualified Mental Health First Aider.

Find out more: